- Home

- Jacqueline Kent

A Certain Style

A Certain Style Read online

JACQUELINE KENT was born in Sydney and grew up there and in Adelaide. Originally trained as a journalist and broadcaster for the ABC, she has been a book editor and reviewer and has a Doctorate of Creative Arts from the University of Technology, Sydney. As well as biography and social history, she has written fiction for young adults. A Certain Style won the 2002 National Biography Award and the Nita B Kibble Award. An Exacting Heart: The story of Hephzibah Menuhin won the 2009 Nita B Kibble Award. She is also the author of The Making of Julia Gillard. In 2018 she won the Hazel Rowley biography fellowship to write a book about Vida Goldstein.

BEATRICE DAVIS

a literary life

JACQUELINE KENT

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

© Jacqueline Kent 2018

First edition published by Viking in 2001

This edition published 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN 9781742236025 (paperback)

9781742244303 (ebook)

9781742248783 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Lisa White

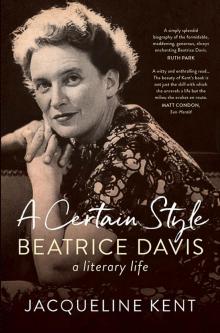

Cover image Beatrice Davis at home at Folly Point, 1951. Photo by Quinton Davis. State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library MLMSS 7638

Printer Griffin Press

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

Contents

Preface to the New Edition: Beatrice Revisited

Introduction

PART I 1909–1937 | Bendigo and Sydney

Little Sweetheart

The Family Intellectual Becomes an Editor

PART 2 1937–1945 | Our Miss Davis

Counter, Desk and Bench: The Story of Angus and Robertson

‘That Woman’

Fighting Words

‘We Must Remain the Literary Hub of Australia’

Living on the Edge: Ernestine Hill

‘Like a Bird Singing, She Sings for Herself ’: Eve Langley

Mrs Frederick Bridges and Miss Beatrice Davis

PART 3 1945–1960 | 89 Castlereagh Street

‘I May Not be a Great Genius … but Nevertheless My Tonnage Cannot be Ignored’: Miles Franklin

Sydney or the Bush: Ruth Park and D’Arcy Niland

Mixing Their Drinks: Women Friends, Women Writers

The League of Gentlemen

Trying Out a Lover’s Voice: Hal Porter

Beating the Bibliopolic Babbitts: Xavier Herbert

No Elves, Dragons or Unicorns: Children’s Literature

Plain Sailing: Angus and Robertson During the 1950s

Bringing the Pirates on Board: The Battles for Angus and Robertson

PART 4 1960–1973 | 221 George Street

The Backroom Girl Moves up Front

Bartonry and Walshism

PART 5 1973–1992 | Folly Point and Hunters Hill

‘I Thought You Needed Me Most’

The Final Chapter

Acknowledgements

Notes

Writers and Their Works

Bibliography

Index

PREFACE TO THE NEW EDITION:

Beatrice Revisited

When I came to look at A Certain Style for this reissue, I wondered whether reading it again would be a bit like climbing back into one’s own bathwater. I needn’t have worried. I wasn’t very far into the book before I realised that the story I wrote almost twenty years ago felt very different from the book I was reading now.

Many things have changed since the book first saw the light in 2001; certainly in terms of publishing. A Certain Style now seemed something of a time capsule, a salute to a time in literary history that has gone.

Of course, A Certain Style was always intended to be a history in a certain sense – the story of Beatrice Davis’s life and work as general editor of Angus and Robertson between 1937 and 1973, as well as the rise and fall of A&R, Australia’s longest-surviving publishers and booksellers, which set up shop in the 1880s. But when it was written it didn’t feel like an historical document. After all, Beatrice had died less than ten years earlier, and because so many of her colleagues and authors whom I had interviewed were still alive, and so much material was readily available, her life and times seemed well within reach. In the memories of those who knew and worked with her and the members of her family, Beatrice was very much alive. And it was easy to find out about her working life, too; I had only to consult the glittering treasure trove that is the Angus and Robertson collection in the State Library of New South Wales, and there were holdings in other state libraries too. I found letters, manuscripts, invoices, book reports and office memos – in short, a wonderful microcosm of life in what was once Australia’s most influential home-grown publishing company.

Beatrice’s fingerprints seemed to be everywhere. It is impossible to gauge how many books she actually edited during her time at A&R, for she worked across so many categories – novels, children’s books, biographies, books of natural history. She was also an influential literary tastemaker, being one of the first judges of the Miles Franklin Award, and she was a member of judging panels for other literary prizes. She edited anthologies of poetry and prose, she gave speeches, she even wrote articles for literary journals. For someone who called herself ‘the backroom girl of Australian literature’, she certainly seemed up front in a number of ways.

Now, however, it’s impossible to look at her career, and the life of A&R, without thinking about the differences in the literary world she moved in.

Beatrice herself was the kind of woman who hardly seems to exist in Australia any more. D’Arcy Niland once summed her up by saying: ‘There goes a gentlewoman, and she’s a little beaut, too!’ It’s the kind of enthusiastic compliment that today’s editors might not necessarily be grateful for – and indeed the word ‘gentlewoman’ is not one you hear much these days. Beatrice Davis, born in 1909, was very much of her class and time. She always dressed beautifully and conservatively – she employed a dressmaker for many years – and she had her hair done once a week at David Jones. In her work, she usually maintained a smooth, professional demeanour to colleagues and authors alike; she was very much in control. Her editorial memos and the letters she wrote that deal with her working life are calm, clear and logical. She belonged to a generation who considered it ill-bred to complain about physical ailments, or treatment by professional colleagues, or lovers, or anything else that might be considered a personal problem. And it’s difficult to think of any book editor today who makes a practice of summoning favoured writers to her pleasant house on Sydney Harbour or a studio on George Street for drinks, beautifully prepared food (and lots of alcohol too), and who would sometimes play the piano for them. She was politically conservative, she believed that politics and religion were not subjects that should be discussed in public, and she r

aised a quizzical eyebrow at the generation of women who followed her, considering 1970s feminism to be rather vulgar and its adherents unnecessarily aggressive.

Fortunately this calm, somewhat chilly persona was not Beatrice’s whole story. She had a wild side, though she rarely spoke about it. She had a happy but comparatively short-lived marriage to a much older man, and many close friendships with both men and women throughout her life. Especially in her later years, after a ‘teeny piece’ of whisky or a somewhat larger piece of red wine, she was apt to declare how much she enjoyed sex. Possibly because of this, there were many rumours about her private life. She was said to be lesbian, to enjoy threesomes with either men or women, and that no male author was safe from her rapacious clutches. These rumours, some encouraged by the writer Hal Porter, others as often-repeated gossip, are impossible to deny or prove at this stage. (She had her defenders, of course: D’Arcy Niland, ever her champion, took severe exception to something Porter said about her at a dinner party, grabbed him by the nose and hauled him downstairs out of the house.) Like most rumours, they are more telling about the people spreading them than about the subject. However, so discreet was Beatrice about her private life that one needs to keep an open mind.

As an editor, Beatrice was widely known as meticulous, a dedicated follower of Oxford Dictionary spelling and grammatical rules according to Fowler’s Modern English Usage. However, she didn’t mind idiosyncratic, ungrammatical language in a manuscript if she thought it was integral to the text, and if questioned she usually stood up for her authors’ right to use it. At the same time, the various state library collections contain manuscripts that she appears to have attacked with a blunt instrument. She did not always consult authors about her intentions towards their texts. Sometimes they grumbled about what they saw as her high-handedness, and she was quite happy to have a robust discussion with them, yielding to their wishes more often than not, and always graciously.

She could be extremely forthright, however, and her home truths – so much at odds with her calm, ladylike demeanour – were often disconcerting. This is perhaps the strongest indicator of the way things have changed in the editing world: it’s unheard of these days for any editor to make similar statements to an author, whatever that editor’s private views may be. Beatrice’s prestige at A&R was such that she could get away with such statements, and her fallings-out with authors seldom lasted long.

Indeed, most of her authors regarded her with admiration and often affection, and finding their letters in the A&R collection was one of the delights of research for this book. When Patricia Wrightson, who became one of Australia’s most distinguished writers for children, sent her first manuscript to Beatrice, she received no reply for a long time. Eventually she followed up with a letter asking ‘the Editor’, ‘What page are you up to now?’ Beatrice laughed, replied, and a fruitful and long-lasting collaboration was the result. Henrietta Drake-Brockman, who lived in Western Australia, would write to Beatrice about all sorts of topics, personal as well as literary. She was always a good friend, as was Xavier Herbert, though the sheer volume of his correspondence could leave Beatrice feeling rather pale. These letters are often revealing, and not always flatteringly so; Hal Porter’s self-consciously Elizabethan script, all curlicues and painstakingly studied effects, shows exactly how he deliberately fashioned himself into the writer he thought he should be.

Beatrice worked on manuscripts entirely by hand, as editors always did in her time – it’s relatively uncommon now, in our digital age. Her handwriting was almost scientifically meticulous (she had trained as an editor with the Medical Journal of Australia), being small, delicate and highly legible, done with a fine-nibbed fountain pen or a mapping pen. I found no annotations in biro, a newfangled writing instrument when she began her career, and one she evidently never adopted.

These days, of course, a book can progress on screen from the mind of the writer to the editor’s work, then to the proofreader, right up to being printed without going anywhere near paper, and it is now possible to read a book without paper at all. Some older book editors these days, possibly those with a masochistic streak, have confessed to the occasional stab of nostalgia for a time when manuscripts were not neatly lined up and typed on computers in Times Roman but were bedraggled and messy, with extra copy attached, whited-out corrections, crossings-out and footnotes added in red. Frequently maddening though these manuscripts were, the process of editing them could be as interesting and surprising as the process of thought itself. It’s impossible to believe that today’s word-processed manuscripts will yield their secrets or their processes of composition in the same way.

Beatrice’s literary world has changed in other ways, too. It was at the end of the 1960s, when she had been running the editorial department for more than twenty years and wielding a lot of power, that Angus and Robertson suddenly had to contend with very significant competition. UK- and US-based multinational publishers opened new offices here, and smaller presses sprung up too. The firm that had more or less had bookselling and publishing to itself for almost a century had to think again.

The story of Angus and Robertson, its rise and fall, is as enthralling as it is exasperating. Why, given the seismic developments in book publishing everywhere, the company could not see that their days were numbered unless they changed radically, will probably remain one of the mysteries of Australian publishing. When Gordon Barton took over the company in the early 1970s, bringing in Richard Walsh to be the chief wielder of the new broom, there was consternation among Beatrice’s friends and authors, and also in Beatrice herself. She did not like the work of new authors such as Frank Moorhouse and Michael Wilding, she thought they wrote entirely too much of what she called ‘roast and boil prose’, and she resisted Walsh at every turn. When she was finally let go, many people in the literary world were up in arms. However, forty years later it is obvious that what Barton and Walsh were doing with A&R – however bruising the effects – was inevitable if the company was to survive.

Now Angus and Robertson no longer exists except as an imprint of a multinational publisher; the sandstone of the Sydney buildings Beatrice knew, including A&R’s headquarters in Castlereagh Street, have been replaced by smooth-faced glass and concrete towers; Beatrice and many of her friends, colleagues and authors are no longer with us. Books are now only one element of a much larger media mix, not most of it, and publishing schedules are much tighter. Gone are the days when Beatrice allowed a book to be published only when she was satisfied that the editorial process was complete, however long that might take – and sometimes it took months, even years. More books are published in less time now, to maintain profits: sometimes it seems that publishers, like the characters in Alice Through the Looking-Glass, are running twice as fast to stay in the same place.

Beatrice believed that a good book would find its readers with minimal effort, and she would have scoffed at the role that marketing and publicity play in today’s book trade. The growth of book clubs, literary festivals, the increasing number of prizes, exposure on mass media – all of these things, which hardly existed in Beatrice’s time, are now essential tools in promoting books. And editors, though less powerful than she was, have paradoxically become more prominent. They lecture in book publishing and creative writing courses and they have their names on the books they edited, a practice Beatrice considered nothing short of reprehensible.

As well as being Beatrice’s life story and that of A&R, A Certain Style is a study in the relationship between editor and author. It’s a rich field for a biographer, shedding a new light on the personalities and attitudes of so many writers with whom Beatrice worked, some of whom are now forgotten while others continue to be celebrated. The nature of this connection, I came to realise, has not changed since the glory days of Angus & Robertson. When an author and an editor sit down together with the aim of making the best possible book, when they must learn to trust each other and the process, all sorts of emotions are likely to b

e unleashed. An author may be suspicious, grateful, annoyed, angry with what is happening to his or her work – an editor might be impatient, irritated with the author’s refusal to understand what needs to be done to his or her words. Editor and author may not even like each other, or they may end up forging an enduring friendship.

The anxieties, the need for encouragement and occasional bluntness – all are familiar to editors everywhere and always have been. And like her successors, Beatrice Davis knew that, even if an author is less than a brilliant writer, the joint work of shaping a manuscript, bringing it through the publishing process to the reader, is often deeply satisfying. Her working life bears witness to her attentive pleasure in exercising her craft.

Introduction

On a cold July evening in 1980 a small elegant woman climbed the wooden staircase to the first floor of the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre on the north side of Sydney Harbour, almost under the bridge. She moved slowly, clutching the rail – the stairs were steep, she was seventy-one and a lifetime of cigarette smoking had made her wheezy – pausing for breath only when she reached the top landing. From behind a half-open door she heard the murmuring voices of about forty young women who were waiting for her to speak to them. Most were in their twenties or thirties, young enough to be her daughters. In one sense that is exactly who we were.

We were book editors. Most of us worked for the Australian branches of the American- and British-based publishers who had dominated the local publishing scene since the early 1970s. Like book editors the world over, we were mainly middle-class women with university degrees. Almost none of us had started our working lives as editors – we were former teachers, librarians, university tutors, researchers – and we all knew we would have been better paid if we had stayed in our original jobs.

A Certain Style

A Certain Style